- What can you tell us about the process? How did you find work with the young actors? What was the initial impulse behind this performance?

When I started working, thirty years ago, we were all young people. Later, I worked with young people a lot and made the performance Generation 91-95 which was successful both in the region and in Europe. Based on the novel by Boris Dežulović, it tackles the topic of the war in these regions, more precisely in Bosnia, between Muslims and Croats. The characters, the then warriors, are played by young people. Instead of casting adults, I opted for the kids who were 16-18 at the time. They were born at the time of the plot and many of them became actors in the meantime. We played the performance in Yugoslav Drama Theatre, but not at Bitef. Out of twelve actors from that performance, eight of them enrolled the Academy to study acting, and out of them, two are now in this performance.

The process was a bit specific. We started with a workshop, not with a text and roles which would be given to certain actors. We started by reading the manifestos by the young mass murderers who usually ended up killing themselves or getting killed by the cops. Bifo writes about them. Actually, he gives just a couple of quotes but we found more material and we found many connections. Bifo helped us understand it more theoretically. We took their diaries and manifestos as a starting point and then we created physical material, we read it to understand it, so that it does not get superficial. At the same time, we were preparing a dramatization but the initial idea was this: let’s see who and what the youth without God today, in 21st century, is and where the new fascist order is being created. Through this process, we were writing an auteur work deeply inspired by the Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s book Heroes. Then, Ivana Vuković and I wrote a text that underwent further changes through the process. Many would call it a post-drama theatre, it has some documentary elements, most of the texts are actually based on documentary material, but it’s not a work of fiction. Of course, that all of those characters find themselves in one space, in one basement, and that they talk to each other and with a teacher - that’s fiction, that’s my imagination, but it was necessary if I wanted to link them without simply enumerating them, it made it possible for me to put them in one frame.

Reading Bifo and Ödön von Horváth, I realized that there is a link which is not necessarily in the murderers but in the character of the teacher. The teacher in Youth without God is actually a man who conformed to the system in order to have a health insurance and pension. In the novel, he’s a relatively young man who has a different opinion but no one to share it with. He’s simply a man who gets caught amidst the turmoil of the creation of National Socialism. Everything is written in the first person. He is actually pretty appalled by what he sees, but out of conformism he is incapable of stepping aside or confronting the system publicly. In a way, that was a motif - all of us, artists included, are conformists. For the sake of survival and some relatively small benefit, you give up some ideals and beliefs and you witness injustice but you don’t do anything - it means that your inactivity actually makes you implicitly guilty for what is happening in the world. And that’s the topic of this novel: it definitely is possible to create a fascist because the people who could prevent it from happening, don’t. In the novel, he finds a solace in God out of guilt, he has a dialogue with God. We even recorded it but didn’t use it in the end. That’s inspiration. I was definitely going to see myself in relation to conformism that we all share nowadays. All of us participate in the system which is destructive in many different ways. Bifo says himself in the book: forgive me, I might be a pessimist, I might be harsh, this might be pornography, and it might be morbid. Actually, what their teacher in the performance says could be a mix between von Horváth’s teacher, Bifo and myself. That’s my intimate link, that left-wing has trouble finding answers. Bifo summarizes the key point we often discussed during the rehearsals: what should you do when there’s nothing you can do? How do you change something when you start losing hope that there’s something you can do? Bifo states that intellectual despair doesn’t reject emotional joy. I see myself as a very left oriented person, and I can see that I don’t have a good story to support it with, while the right-wing with all their radicalism manage to twist and conquer the space, and it’s much easier for them to present their ideas.

- How can theatre influence the community nowadays?

I don’t have an answer to that anymore. We have many different theatres, it’s become very diversified… but the question remains if any of those forms produces anything. I like it when it’s inclusive, when the users become a part of the process, when they become protagonists, it’s a kind of documentary approach. A good example is Generation 91-95. These kids weren’t actors back then, they were just kids, and now they are actors. Through the process, they got something and possibly even changed something in the world. I’m not sure I’d call it a mega success, but if you do manage to change the opinion of just one person in the audience, it’s still something. The power of theatre is relatively insignificant, it doesn’t reach the majority, it works for the benefit of the elite which can afford it and already has the cultural capital in its possession. It’s all very cynical. So the question: “What should you do when there’s nothing you can do?” is a question relevant for theatre too. You can’t approach theatremaking as a job, because it’s a vocation.

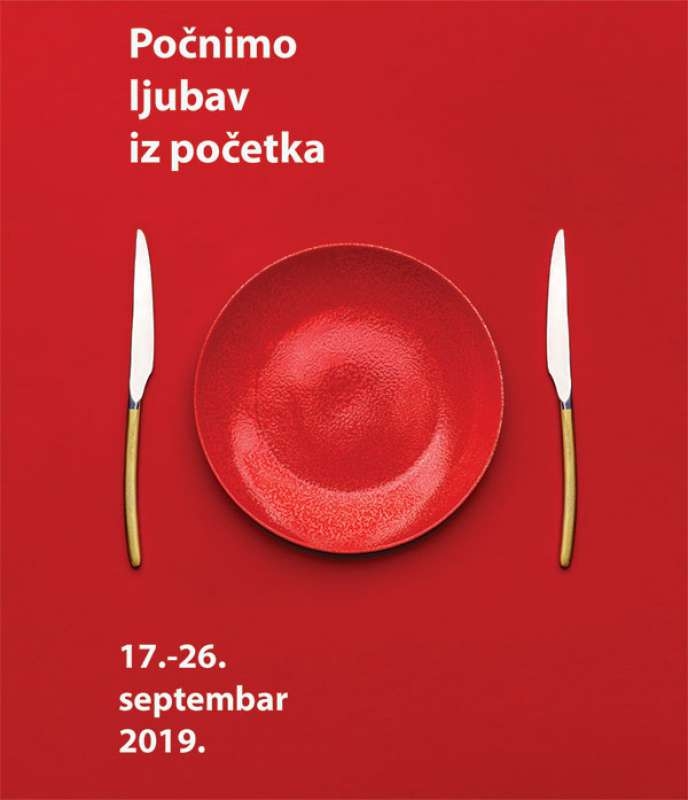

- How do you like this year’s Bitef slogan?

You have to have a slogan nowadays, something people can take as a concept. It is linked to the present moment, the question whether we can change anything in the world, whether there’s anything we need. Love is really important, it fuses many things, it’s not just about intimate love, I think that the reference here is wider than that. Even politically speaking, love is very important, as a notion, while someone will understand it only in religious terms. There’s no revolution without love, that’s absolutely true. This slogan should mean a lot, also - let’s start revolution over. You can identify love with many things, which is why I think it’s good. And then again, it’s also the title of the song.

- What would be your advice to your younger colleagues?

As the teacher says: don’t participate, don’t play that game, trust no one, not even me. You can’t really be sure you’re in a position to offer any advice to anyone. What I do think, though, is that young theatre makers should try and keep what made them enter the art in the first place. If they chose something that shouldn’t be a job but a vocation, they must never forget that it’s a vocation! Theatremaking is a vocation!

.jpg)